Wilmington Friends Meetinghouse, Fourth & West Streets, Wilmington, Delaware

Early Wilmington's population as predominantly Quaker. On the highest piece of ground they built their meeting house and settled around it in an area of the city now known as Quaker Hill.

The Quakers were among the most prominent families in Wilmington and their meeting house was one of the most important religious structures in the city.

The present meeting house is an excellent example of the type of structure built by the Quakers for worship in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

They stressed high quality workmanship and simplicity of detail.

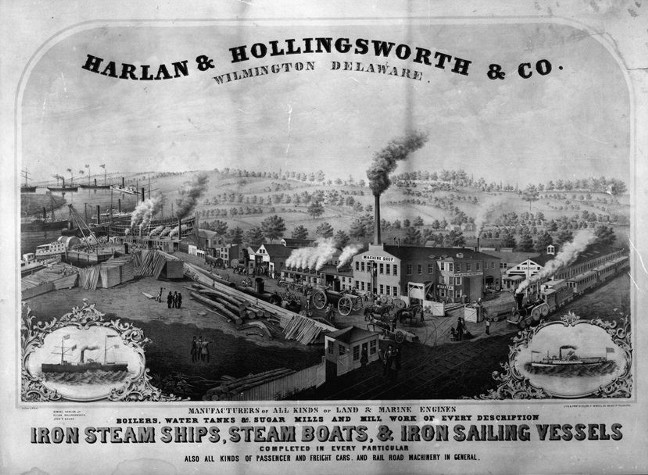

The Harlan & Hollingsworth Co. began the manufacture of railway passenger cars in 1836 and commenced iron shipbuilding in 1843.

Energetic management, competent production, and expanding markets for its products established the firm as Wilmington's leader in both fields. In 1845, Harlan & Hollingsworth launched the "Bangor," the first American-built iron vessel for deep sea use.

By 1860, at which time Wilmington assumed pre-eminence in the field of iron shipbuilding, Harlan & Hollingsworth was the city's leading concern in that industry.

During the second half of the 19th century, Harlan & Hollingsworth established a national reputation for high-quality railway passenger cars, iron-hulled steamers, steam engines, and boilers.

By 1880, the firm's work force numbered over 1,000 and the plant, situated between the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Christina River, spread over 43 acres on Wilmington's south side.

In 1904, high cost of materials, labor unrest, and problem-ridden contracts brought the sale of the firm to the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation.

Production of ships ceased in 1926 and car manufacture ended in 1939.

Few buildings can boast of such a record of continual community service as Wilmington's Old Town Hall.

From its erection in 1798 to the present, it has been a viable part of the City. It has kept pace with the needs of its citizens by serving as both a political base, a cultural center,, and the City Goal.

Today, it is one of only three extant public buildings in the area erected prior to 1800.

It may be considered an architectural hallmark of historic Wilmington, for its refined details and graceful proportions make it exemplary of Georgian architecture.

The A.I. du Pont estate, known as Nemours, was constructed in 1909-1910 by Alfred I. du Pont (1864-1935), great-grandson of Eleuthere Irenee du Pont, the founder of the Du Pont Company in America. The Beaux Arts-trained firm of Carrere and Hastings designed the eighteenth-century French-style mansion, upper gardens, and estate grounds. The firm of Massena and du Pont designed the lower gardens between 1929 and 1932. Massena and du Pont also designed the memorial Carillon Tower in the mid-1930s, in which are buried Alfred, his third wife, Jessie Ball du Pont, and her brother, Edward Ball. The firm also served as associate architects for the design of the Alfred I. du Pont Institute, a hospital for crippled children constructed on the estate grounds in 1940. A sizable addition to the hospital was completed in 1984. The approximately 320-acre property is roughly divided by usage with the Institute and the tower to the north and the mansion and gardens to the south. The estate is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Nemours Historic District.The significance of the A.I. du Pont estate is threefold. First, it stands as a physical testimony to the personality of Alfred I. du Pont. The likes and dislikes and the strengths and weaknesses of the man greatly impacted the design, construction, and operation of the estate. Indeed, any analysis of the estate cannot be separated from an understanding of the life events that shaped the character of its owner. Alfred's interest in the French heritage of his family, his interest in historical matters generally, his equal interest in modernization, and his own inventiveness in the areas of machinery and technology are all manifested in the buildings and grounds of the estate.

Second, the estate stands as a physical example of the American country house movement, especially the stately homes type of architectural design practiced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This type stressed adherence to the principles of the Ecole des Beaux Arts with an understanding of current advances in building technology. Its architects designed large, ostentatious estates for the wealthy elite of business and industry. While not a preeminent example, nevertheless the Nemours estate is a fine representative of its type and period.

Third, the estate stands as a physical reminder of the class dynamics and consciousness of Alfred and his contemporaries, yet it also demonstrates his personal attempts to reach beyond his class through philanthropy. The wealthy elite of Alfred's day sought to cement their position in society through exclusive living, ties to early America or Europe, pursuit of leisure activities, and accumulation of land for leisure agriculture: gentleman farming, horse and livestock breeding, and gardening. Alfred was certainly a product of this thinking, yet he also demonstrated a lifelong concern for those in society unable to help themselves. His philanthropic efforts on behalf of the elderly and the dispossesed during the Depression are indicators of this. Moreover, the Nemours estate today stands as the ultimate work of his philanthropy, both in the Institute for children and in the opening of the mansion and gardens to the public for their education and enrichment.

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New

Hampshire

New

Jersey

New

Mexico

New

York

North

Carolina

North

Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode

Island

South

Carolina

South

Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West

Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

Washington

D.C.

Home